The Climate Crisis And Its Impact On Marginalized Communities

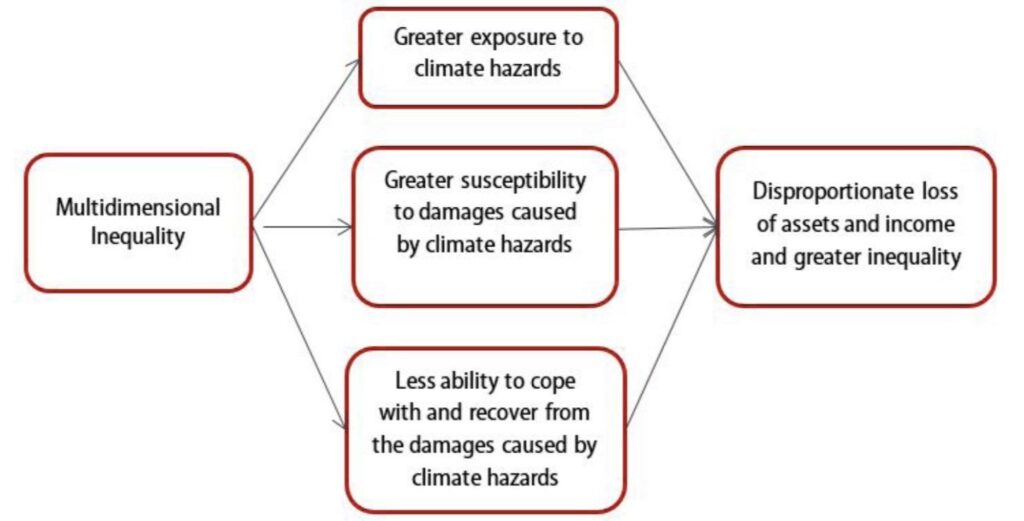

The interconnectedness of climate and social justice can be underlined in three main concepts:

Disadvantaged groups have been disproportionately harmed by the climate crisis for they are:

- Located in areas with greater exposure to climate hazards

- More susceptible to damage caused by climate hazards

- Less able to overcome or address damages caused by climate hazards.

To put things into perspective, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has discovered that warmer temperatures exacerbate flooding due to increased precipitation, more frequent hurricanes, and higher sea levels. Coastal areas and deltas are most prone to flooding and erosion, yet disadvantaged groups are inclined to reside in these regions because they are unable to afford living in high-elevation zones; Moreover, their homes are more susceptible to being torn down or washed away due to being built using frail materials, as opposed to urban architecture that employs brick and concrete. A salient factor that limits marginalized people’s ability to cope with and recover from damages, is that the affluent populace can afford insurance and have any damages be covered, while those less fortunate are often unable to afford the same protection, forcing them to suffer greater loss.

![[Photo: Partially submerged village in the mangrove-covered delta region, the Sundarbans, in May 2009 on the northern coast of the Bay of Bengal]](https://ecosphere.blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/image-2.jpg)

In addition, low-elevation coastal zones tend to be subjected to salinity intrusion (when saltwater from oceans or seas seeps into freshwater sources like rivers or aquifers, making the water salty and unsuitable for drinking or agriculture), causing 70 percent of farmers[1] who rely on the landscape for farming to scale down or completely cease operations. This would, as expected, further deplete the local communities’ food supply.

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL INEQUALITIES IN REGARD TO CLIMATE CHANGE

The upper echelon possesses substantial resources that can aid them in weathering the effects of climate change, whereas disadvantaged groups are less able to sustain themselves through private assets. In turn, underprivileged people rely on public resources; yet those in positions of power tend to control state power and shape policies in a way that would benefit them most, further draining disadvantaged groups’ means to protect themselves from climate hazards.

The idea of “disadvantaged groups” is multifaceted, for a certain position of disadvantage is all but a single link in the extensive chain of marginalization. For example, gender inequality leads to economic inequality (the most significant is the pay gap), as racial inequality, as well as prejudice against sexual orientation and identity, does. Simply put, political inequality is a breeding ground for economic inequality. The climate injustice hurts women, the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, as well as people of color, making it less accurate to only label the victims as “economically disadvantaged”.

Rebuilding Burnt Botany And Bridges

There’s no denying that the issue of climate change and social justice go hand-in-hand. Tackling social injustices aids in mitigating the damages of global warming, and dealing with global warming helps reduce social inequality– a win-win scenario. Climate change is most detrimental to groups who have played the smallest part in it, while the rich remain shielded from the consequences of their environmentally damaging lifestyles. Although the interconnectedness of social and climate justice has yet to be fully understood, not all is lost. With a deeper understanding of both the physical and social damages caused by the climate crisis, we can better address the dangers that grow more daunting than ever before.

References

Abdi, Omar A., Edinam K. Glover and Olavi Luukkanen (2013). Causes and Impacts of Land

Degradation and Desertification: Case Study of the Sudan. International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 40-51.

Anbarci, N., Escaleras, M., Register, C. (2005). Earthquake fatalities: the interaction

of nature and political economy. Journal of Public Economics 89, p 1907–1933.

Barbier, Edward B. (2010). Poverty, Development and Environment. Environment and

Development Economics, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 635-660.

___(2015). Climate change impacts on rural poverty in low-elevation coastal zones. Policy

Research Working Paper no. 7475. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Patankar, Archana (2015). The exposure, vulnerability, and ability to respond of poor households

to recurrent floods in Mumbai. Policy Research Working Paper no. WPS 7481. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank (2002). Poverty and Climate Change: Reducing the Vulnerability of the Poor

through Adaptation. Washington: D.C.: World Bank.